‘Call this a moment for action, not a crisis.’

BERLIN

Unfortunately, many human rights groups, aid organisations, and media outlets are repeating the mistakes of 2015 and 2016 by using messaging that inadvertently triggers fear of refugees. This time, instead of fuelling a sense of crisis, we should build a narrative focused on solutions to create confidence in our societies’ ability to support refugees.

Right now, we’re seeing an outpouring of support for Ukrainian refugees. But history warns that the current goodwill will likely dissipate over time if people in host countries start to feel overwhelmed by a mix of crisis, urgency, and fear – leaving the door open to divisive politicians who scapegoat refugees and harsh migration policies that cause harm to people seeking safety.

Once again, daily headlines are sounding the alarm about the ever-growing number of people fleeing the war in Ukraine. UN agencies constantly repeat that this is the “fastest growing refugee crisis since World War II” and that it could soon turn from crisis into “catastrophe”. Meanwhile, the media ask how Europe will handle this “wave” or “flood” of refugees.

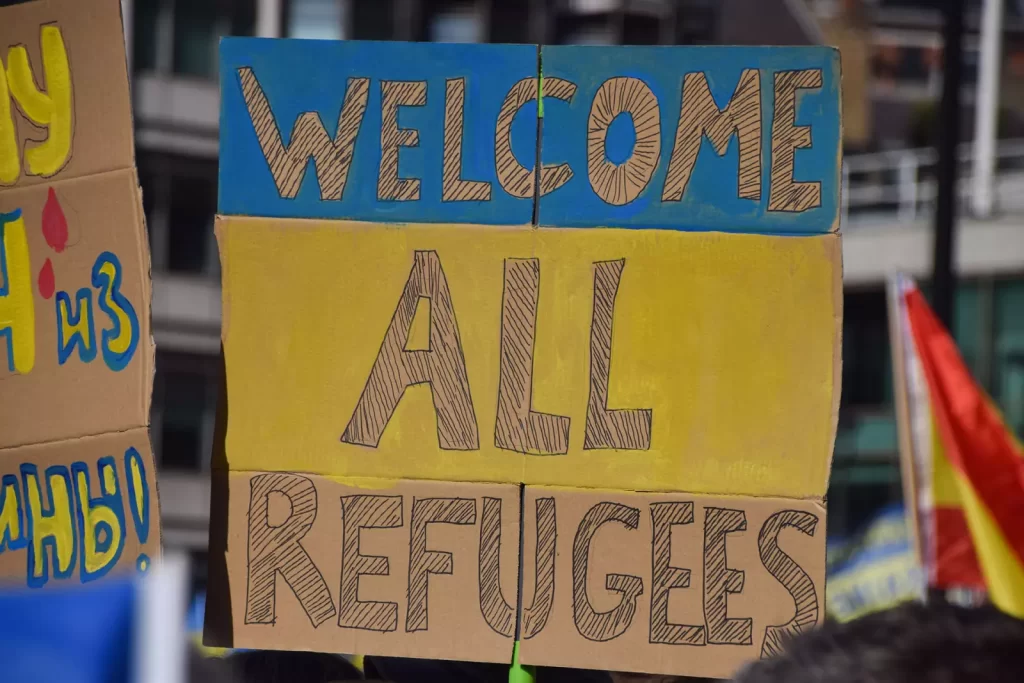

This language of weather and climate disasters is often accompanied by images of large crowds of distressed people. The tone and visuals subconsciously make people in host communities feel powerless and want to keep the problem at bay. Even the less dramatic language used to talk about the movement of people across borders, such as migration “channels” or “flows”, conjures destructive natural forces, and the responsibility of countries to receive and host refugees is almost always referred to as a burden.

Instead of depicting the scale of the crisis as dire to the point of being unmanageable, we need to tell stories that nurture the goodwill that encourages countries to open their doors and continues to motivate people to go to train stations to help strangers.

Brain science shows us that people who feel hopeful are more likely to feel compassion. When we feel fear, our brains are wired to focus on our own safety and self-interest. In political terms this translates too easily into seeing people who are fleeing from danger as a potential threat.

In the face of situations like Ukraine, it’s natural to use fear-based messaging that creates outrage to shame governments into action and sympathy to raise funds from the public.

But outrage burns out fast. The Mindworks Lab – created by Greenpeace to understand how the human mind works during emergencies – talks about a crisis timeline, where public response moves from a “honeymoon” phase of mass support to disillusionment and compassion fatigue. Stories about faceless masses of people on the move hasten that process. Message testing consistently shows that care and compassion are more effective frames for this conversation than eliciting pity.

Without a clear story about how we can solve the situation, constant crisis messaging risks creating despondency. Worse still, it can make people support drastic, cruel measures that offer a false sense of control: such as pushing people back from borders and sending refugees to island detention centres, as Australia has done and the UK is currently discussing.

This is what we saw happen in 2015 and 2016: Following an initial moment of welcome, voices calling the arrival of Syrian refugees to Europe a “crisis” and an unmanageable “burden” drowned out the humanitarian impulse to provide safe haven, paving the way for the rise of authoritarian-minded populists across the continent.

To avoid repeating this scenario, we need people to believe in a human-rights-friendly solution. Humanitarian, refugee, and migration groups need to explain how we can make supporting refugees work for all of us. That is why the most important message people need to hear when people are fleeing war is what German Chancellor Angela Merkel said in 2015, “We can do this!”

This means fewer urgent updates on the numbers of people fleeing Ukraine and other conflicts, and more about getting people ready to welcome them. Yes, we absolutely have to talk about the world’s problems. But how we talk about them can either make people feel hopeless or convince them that there is something we can do about it.

We have to get away from talking about countries like containers with a limited amount of space. Instead, we have to talk about how a society’s strength is measured in its capacity to care for people. It’s also important to let people on the move tell their own stories, talking about their resilience and their aspirations so that we can relate to them as equals rather than pity them.

Better yet, focus on the real issue here: whether host countries are welcoming enough. Creating a stronger culture of welcome is the only way to replace narratives and policies of cruelty and indifference towards people on the move.

Problems occur when fear makes communities closed to people who are different. By amplifying voices and stories of people who want their communities to be open, diverse, and welcoming, we can model welcoming behaviour, nurture welcoming attitudes, and change the narrative around migration. We can then work on extending that welcome to all people on the move.

People need to see the solution in order to support it. This means that humanitarian aid organisations and human rights groups can make a big difference by showing images – in their press releases, marketing content, social media, and when speaking to the media – of a world where people move and are welcomed through small, everyday actions. The media can take a similar approach. When we, our friends, family, and neighbours start seeing these stories and repeating their message, humanity starts to become our new political common sense.