PBB’s Training of Trainers, a hybrid “learn-teach-learn” co-creative program for displaced and migrant artists based in Berlin and coming from all around the world, kickstarted last week with a first session. Facilitated by Isadora Canela, a Brazilian visual artist and lead creative curator of PBB Germany, we dived into discussions about decolonization, art as an emancipatory practice to create new imaginaries and narratives to face contemporary challenges, networks and teaching models based on horizontality and co-responsibility.

“Learn Teach Learn” co-creative program

The Training of Trainers concept is born through exchanges with migrants, refugees and displaced communities in Europe and MENA regions, which shed light on the over-abundance of certain types of training courses, often stemming from a default neo-liberal capitalist lens, which often fail to tap into the skills and knowledges already possessed by the communities. Indeed, migrants often already possess extensive skillsets and expertise, and are interested in sharing these with their peers. Learning to teach those skills, thus, appeared to be a common need and gap in training offers.

Furthermore, while the focus often lies on corporate skills, we looked at the importance of skills that are situated outside of this market logic, but crucial to the communities and individual well-being. Our exchanges showed that creative, artistic, cultural and well-being practices appear to be largely absent in the diverse training offers, while representing areas of significant interest for displaced communities. It also seems that spaces oriented towards the sharing of creative practices are also where people can let go of social barriers, connect on a deeper level and create sustainable networks.

Key to the concept, was thus the idea of designing spaces of co-creation and exchange for migrants, refugees and displaced people to explore and expand their artistic practices and skills – both as a mean of self-expression, as well as a way of relating to the world in creative, innovative and affective ways. The ToT was developed as a response to this gap, with the aims to create a rizhome-like [1] artistic network for displaced artists to meet, share skills, stories and knowledges, and connect around creative practices. ToT aims to bring its participants practical teaching skills and knowledge (about funding landscape, how to budget, how to pitch a project) to transform art practices into potential income generating activity.

But more than that, ToT aims to challenge hegemonic hierarchies and power structures at the core of education, and seeks to become a horizontal network of teachers and learners, a space for co-responsibility, vulnerability, reflection, learning and co-creation.

First ToT session: a theoretical exploration to decolonize arts and education

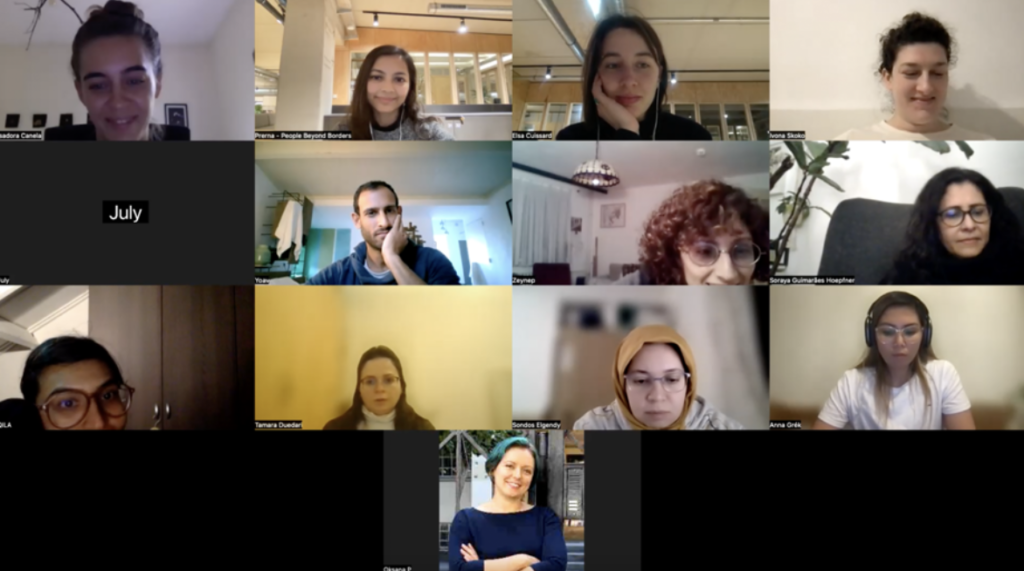

On 7th Feb, 2023, our group of 11 participants (one man and ten women, or as he nicely described it: “a matriarchy”) met online with our team to kick off the first stage of the program. The group could be seen as a micro-ecosystem, transcending age groups, cultures and disciplines, with participants aged between 27 and 49, coming from diverse places – Brazil, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Syria, Ukraine, Turkey, Israel, Egypt, Columbia, Malaysia, and the Philippines – and with various artistic backgrounds, from painting, drawing, singing, writing, linguistics to visual arts, digital media, photography and film.

The first module of the program, titled “Thematic Framing”, focuses on shaping the contours and foundations, and sowing the theoretical and practical seeds for collectively building (with and in) the ToT space. Reflecting on the role of art in disrupting the hegemonic and colonial paradigm, and in recentering and valorising subjugated knowledge and histories, we explored the concept of decolonization, and its practical ramifications for ToT.

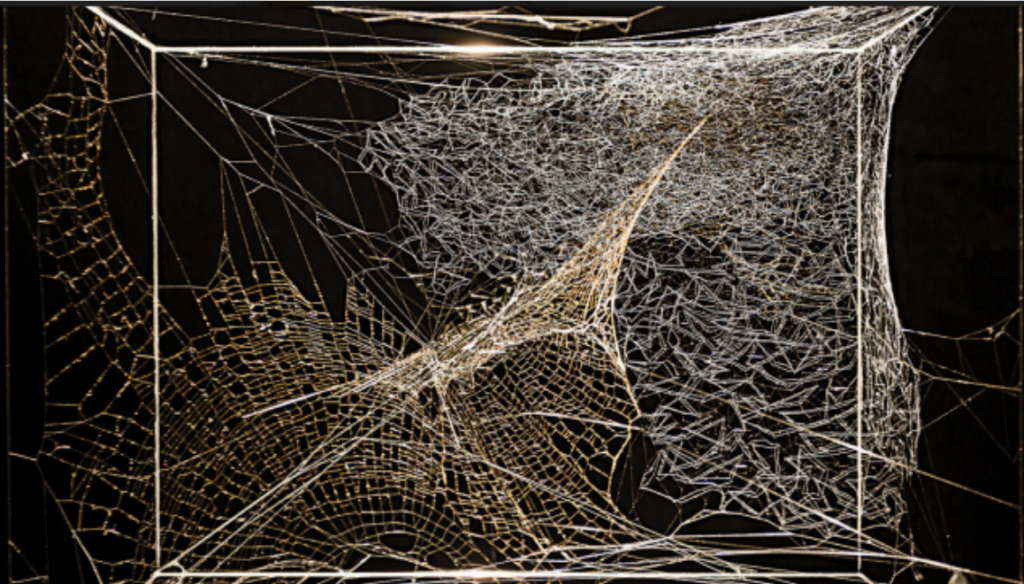

We looked at art works who are calling us to ask ourselves: How can we build on current conditions to sow new futures on the ruins of colonialism? How can decolonial practices be embedded in the millions of years of existence of ecosystems and in indigenous practices of care and interdependence?

And most importantly:

How can ToT be a space for experimentation to embrace all these questions? What does decolonization look like, or mean in reference to our artistic and collective creative practice, and our learning and teaching space? How do our multiple identities, life trajectories, realities, affections and expectations intersect with this project, sometimes reinforcing it, sometimes colliding?

Navigating disorder as a collective, to create new agreements

Disrupting hegemonic rational, efficiency oriented and productivist modes of social organization to invent something new creates a vacuum, a space of potentialities, but also of disorder. Navigating the mess as a collective can be both rewarding and challenging.

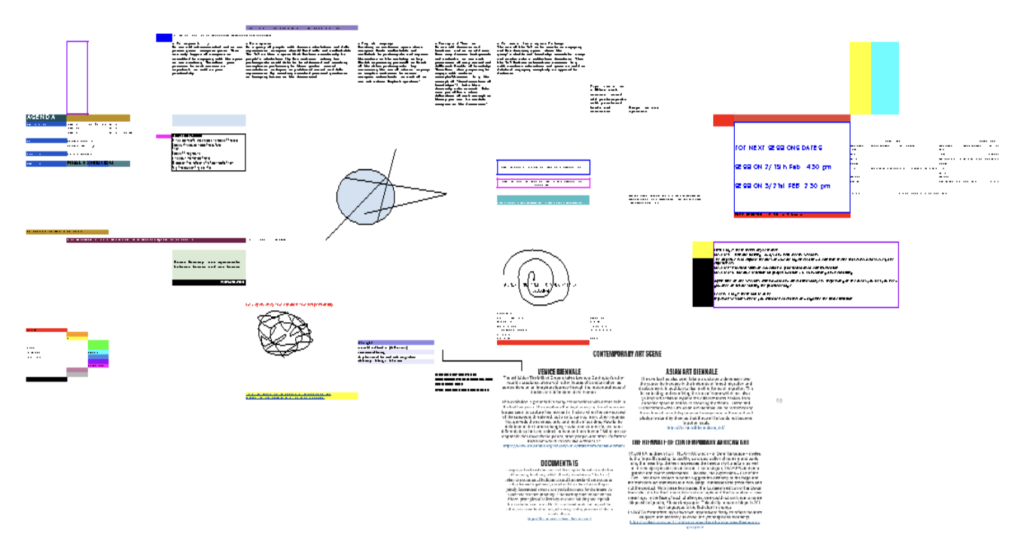

Mirroring the ways in which the artist Vera Molnar plays with computer generated geometries to break regularity of shapes in her work “Computer Rosace Series” (1974), Isadora proposed an exercise: to subvert the Excel spreadsheet – a productivist tool for corporate efficiency-oriented mode of information management and a metaphor of capitalist social organization, be used to create a collaborative and disruptive aesthetic diary. The altered spreadsheet would become the collective record and visual artifact of the group’s reflections, arising questions and challenges, dialogue, individual affective reactions and self-expression, for each ToT session.

Throughout the session, and like an intense living organism, theoretical discussions on colonial visualities, and the mechanistic social organisation of the capitalist model metamorphosed into a deep field of reflection on efficiency, frustration, the limits between coordination and imposition, comfort and collectivity.

“I appreciate the framework of decolonizing the ways we work together, but I also notice for myself that it’s a quick jump from linear more structured ways of working to something completely different which creates a lot of frustration [sic] ” – Oksana (participant artist)

While consumerist capitalism is founded on its ability to deliver immediate satisfaction to the individualized needs and desires it manufactures, it could be argued that the experience of a sense of collective frustration could hold in itself a subversive value.

However, as she later argued:

“In this practice, one thing to consider is the question of power and resources when we do want to push ourselves and the people we may be working with to a certain boundary. You mentioned that this frustration and discomfort with the sheet is a metaphor of our reality, and I would argue that as displaced persons we are dealing with enough frustrations in our daily reality that maybe a learning space is where we can have more ease and that’s one way to look at it, if you acknowledge that the people you are working with are coming from unprivileged or unsettled contexts” (Oksana)

Highlighting power imbalances and resource inequalities, the discussion shifted the notion of frustration to an affective state and reaction to unequal positions within power structures, and multi-dimensional discriminations related to migrant status, resulting from a constant need to overcome barriers and obstacles of different kinds.

These power structures also manifest themselves in the microcosm of our ToT space, as one participant noted, raising the question of the organizer’s roles in a proposal of horizontal and decolonial exchange?

“I think it’s interesting that we are having this conversation, because the discussion is to decolonize, and when you think about decolonize, funnily enough, essentially there is a hierarchy here because you are the presenters and we are the trainers, and it’s interesting to think of it contextually, where you are presenting something and breaking a barrier for us, but then that becomes a barrier in itself, and how do we adapt to it, and innovate with it in our work?” – Qila (participant artist)

Unfolding reflections

This collective excel spreadsheet exercise raised fundamental questions:

How can we subvert a centuries-old colonial logic so deeply rooted in us, and guiding us along the paths of efficiency and productivity, without this rupture being yet another point of discomfort and frustration? What does a disruptive and experimental space that nurtures a sense of comfort and familiarity look like? How to create sustainable collective agreements for the individuals that form this ecosystem?

As we wrapped up Session 1 and prepare for Session 2, many of the answers seem to lie in the process itself, and in its unfolding: a balance that makes space for frustration and divergence of perspectives, while building affection, empathy, care and kindness into the premises of the collective coexistence. As one of our participants said, it is perhaps in allowing the process to breathe, like a living organism, that it can unfold and transform us.

“My first intuition is to take the smallest place in the process and let it breathe and see how to adjust. I do it because it will require a lot of patience and empathy […] so I just try to see how it goes and have a little faith in the process” – Soraya (participant artist)

These were some of the reflections that emerged from the first session, an encounter, a plurality of mental, emotional, practical and theoretical open doors. And far beyond the possible answers, the potency of the discussion is already in itself a new possibility of experience in society. As one of the participants said: “possibilities are higher than reality”.

We welcome the possibilities that emerge as possible realities.