During the Summer, I travelled to Belgium and Cardiff to speak to people who are seeking asylum in Europe to find out why they wanted to settle in Belgium and the UK.

At a sleepy port town 3 hours from Antwerp in Belgium, people are risking their lives to try and reach the UK in order to seek asylum. Zeebrugge found itself in the news in October 2019 when 39 people were found dead in a lorry container in Essex. The lorry had traveled from the Belgian town the day before and the little community was front-page news in British media. But the lives and experiences of the 39 people were scarcely discussed.

In August, it was reported that 1,000 migrants arrived in the UK between 4th and 13th August. Media outlets also discussed the UK’s £5.5 million budget dedicated to stopping crossings to the UK from France (and Belgium).

Despite the tragic events in Essex and its subsequent media coverage, Belgium is barely mentioned in these news stories.

Mehdi Kassou, founder of Citizens’ Platform for the Support of Refugees in Belgium, estimated that there were over 1,000 migrants-in-transit (people moving from one country to another but staying in a third country during their journey) in Belgium with approximately 600-800 individuals in Brussels. If people are embarking on such dangerous journeys, surely they have stories to tell and surely they are worthy of recognition?

My family has spent a lot of time in Belgium over the last 2 years. Having previously volunteered with refugee charities, I wanted to find out more about the experience of people seeking asylum who are presently in Belgium and why they continue to try to reach the UK.

“If I can cross to England, maybe the first thing I will do is to get to a university, to a college to continue my studies… Many companies I worked in [Algeria], but without a certain level of studies, you cannot advance. That’s why I’m trying to get a little bit more of knowledge to try to stabilise my life.”

Farid*, a 28-year-old from Algeria who I met at Zeebrugge, was visiting the home of Pastor Fernand Marechal. When we chatted, he told me why he wanted to go to the UK. He said that he had tried to enrol at universities in France and Belgium before he started trying to go to the UK and that the goal of reaching England was not his first choice.

Speaking to Pastor Fernand about this, I asked him his thoughts. He said that the people trying to reach the UK tell him, “In England, we can work, we can do everything“. He said that, for them, it is “England or dead.”

Pastor Fernand dedicates much of his time to providing food, clothes and weekly medical consultations to asylum seekers who are visiting Zeebrugge. When discussing this work, he told me that the town was accustomed to the community of itinerant people trying to reach the UK. So ingrained in their community history was this journey of people seeking asylum that they had art installations in the church commemorating the lives of those who died trying to cross the sea.

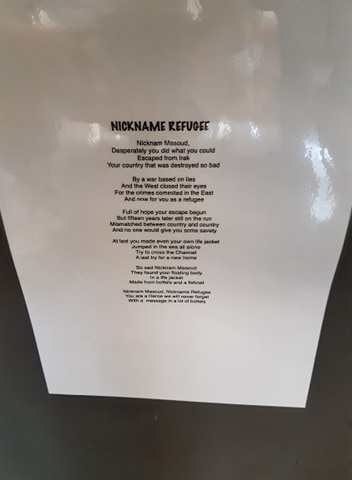

A stark example of this was the poem ‘Nickname Refugee’ beside a sculpture and art installation including a dummy on a stretcher wearing a lifejacket made of plastic bottles – as was worn by the young man nicknamed ‘Massoud’ who drowned in the North Sea and washed up on the shores of Zeebrugge.

But not all people who are seeking asylum are trying to reach the UK. Some choose to give up.

While in Antwerp, I met with Ali*. Ali worked as an interpreter for the US Marines in Afghanistan until 2015. Five months after ending his job, he felt it was not safe for him in Afghanistan and travelled (mostly on foot) to Denmark. He waited in Denmark but his asylum application was rejected and so he travelled on to Calais (where he tried to reach the UK) before settling in Belgium.

“When I was in France, I tried for [the UK]. I have been to Calais. I’ve been waiting for two months to go to there, but I tried, two times, to go to channel… I wanted to cross that and to get into the container. I was so close to the container that I go, get into, suddenly you know, there was an alarm was ringing. And then some dogs with security guards. They just came and they just find me. And then, they just take me, put me in the car and then after that, they just say to me like don’t come. Don’t come again.”

However, despite his efforts, Ali told me that he felt trying to cross the Channel to the UK was now too dangerous.

“Nowadays, it’s become really hard to cross the border because I’ve been heard about a million monies given to France and Belgium to protect the border, and do not let the people across… I wouldn’t [try again] because it’s really hard to be in the container for 20 hours or maybe 40 hours, maybe 30 hours, is really hard. I cannot breathe.”

As with Farid, the UK was not Ali’s choice of a destination to travel. Both men had faced rejection from another European country before even attempting to cross the Channel. I spoke to Robin Vandervoordt, an assistant professor in refugee migration studies at Ghent University, about the wider context of this experience and how the experiences of Ali and Farid are not isolated accounts.

“For [many people seeking asylum and trying to reach the UK], they have applied for asylum elsewhere in Europe but they have not been granted asylum, after which, they try to go to the UK to apply for asylum there. But at the same time, there are other people granted asylum, or whose asylum procedure have been running for a year or two year, who have found themselves living on the streets, in destitute conditions that are unsafe also for their family. And then, in both cases what really happens, they have travelled to Europe, they don’t feel like they can go back, even if their asylum application has been rejected, and then their last bit of hope shifts onto the UK.”

And, people do reach the UK.

The necessity of understanding ‘the arrival’ part of a person’s journey felt necessary in the process of researching the documentary. I had been working so hard to understand what causes people to risk their lives to reach the UK but what next? What happens to someone if they survive such dangerous journeys.

I travelled to Cardiff to speak to Salma*, a young woman who arrived in the UK last year. Salma was smuggled from Brussels to Cardiff in November 2019 while pregnant with her son. After sleeping rough in Parc Maximilien, Brussels for a week she paid traffickers to help her into a lorry container where she sat for hours with two other people before she arrived in the UK. She had her baby during lockdown but her husband was detained in Belgium after he was caught trying to hide in a lorry container.

“Where do I go, I don’t know. I have to come here to save my life. In Germany, it is not ok, I can’t stay in Belgium, so I have to come here.”

Salma didn’t want to leave Germany, however, she felt life was no longer sustainable after her asylum application was rejected. “I need to, I want to live here [in the UK]. I don’t want to go anywhere else. Again, again, travelling, I am tired… Nothing’s new. You go here and here and here. I want to see here what will happen.”

The wider context of this experience was explained to me further by Holly Taylor, a member of the Welsh Refugee Council.

“There’s this impression that exists in people’s minds that people are sitting on the African shores of the [Mediterranean Sea] with holiday brochures looking at what benefits are available in different countries. And the evidence shows that that’s just not the case… Many people won’t leave their own country and have a destination in mind, they will meet people on the way, they will have conversations, they will hear things on the way that will shape their decision. People don’t know what to expect when they make those migration journeys.”

The arrival in the UK is not a relief for many people either, according to Holly.

“We speak of the asylum system itself in the UK as traumatic on top of the trauma [people seeking asylum] have experienced in their own country that has caused them to flee, the trauma they will have experienced on the migration route. Then, they come to the asylum system in the UK and, instead of finding a place where they can start to recover and move forward, actually, they are stuck in limbo.”

During the final fortnight producing and editing this documentary, the news was flooded with stories about migrants crossing the channel in boats from France. The focus of the narrative from media outlets was on the journey itself and the reactions of governments. Little was said about the lives of the people who could drown in a boat and less was said about what would happen to them, successful or not.

Three weeks after our first meeting, Salma contacted me again with good news: she had been moved from her cramped hotel room with her baby into shared accommodation. After speaking to Holly about the difficult situation in the UK, I wanted to know what Salma hoped for.

“I dream of a family. In a year, not two years, it’s too much. Hopefully next year, my husband is also with us so we are living our life, nicely, perfectly… Of course, if my husband is here, I can go, I can have time for going to school, for anything to do. But if I am alone, it can’t be easy. Yeah, it can’t be easy.”

The documentary (embedded below) is only a snapshot of one kind of experience people have when trying to seek asylum in Europe. I spoke to other people, those choosing to stay in Belgium, who told me about the challenges they faced getting to Belgium and living in that country’s asylum system (another documentary, perhaps).

From a journalistic perspective, telling stories (or creating the space for people to tell their stories) during a global pandemic was hard. Few people want to speak to a journalist on a good day, fewer do so when there is the threat of a virus spreading. But with a trusty lapel mic and some social distancing, this could be managed.

However, the greater challenge (which still remains) is discussing this with people and emphasising that this is a human experience. Tallying numbers of people on boats is a poor representation of suffering that has been endured by thousands (and is still being endured by so many more) all for the hope of safety. Asylum systems rest on the need for categorising someone’s experience in a way which can be processed and it is so easy for us all to get caught up in these terms.

However, I hope, at its heart, this documentary does what I planned from the start: puts the voices of those who are not seen and not listened to at the centre of the narrative.

* The names with an asterisk are pseudonyms used to protect the identity of the interviewees in a vulnerable situation.